25 years on, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon still unites East and West

When Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon director Ang Lee looks back on the famous martial arts film a quarter-century later, he can't believe what it took to make the Oscar-winning movie.

"I honestly don't know how I did it. The energy, the emotion, the scale; it's something I can no longer replicate. It's a hidden dragon in myself," Lee said.

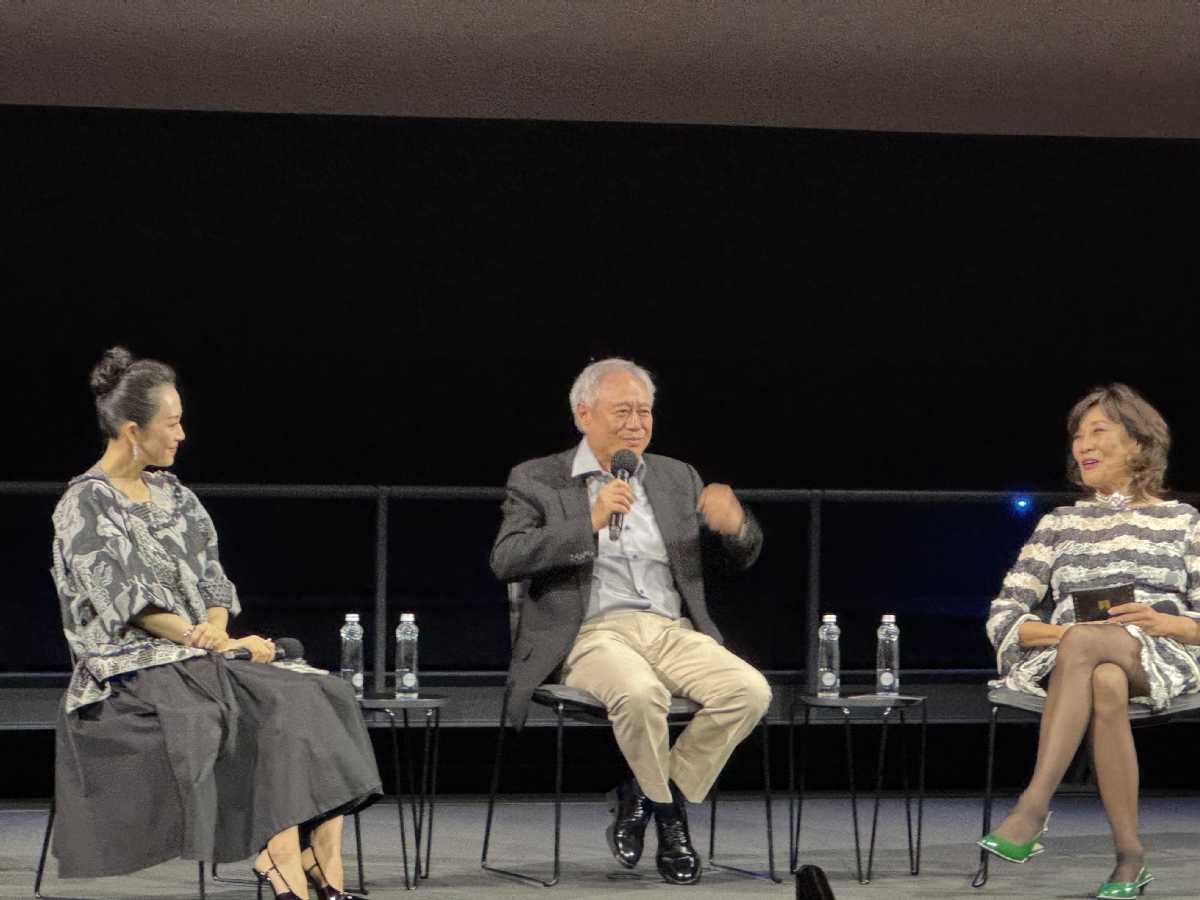

He spoke before a special screening at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on May 9, marking the 25th anniversary of the Chinese-language film.

The event was part of Raising the Lantern: A Celebration of Chinese-Language Cinema, a six-week series highlighting Chinese-language films submitted for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film over the past 35 years.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon received 10 Oscar nominations in the 2001 Academy Awards — then a record for a non-English language film — and won four, Best International Feature Film, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score and Best Art Direction. Lee was nominated for Best Director.

Janet Yang, president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the first Asian American to hold the post, described Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as a landmark achievement that continues to resonate globally.

"Lee's film is emblazoned in our hearts and minds as a singular leap in filmmaking," Yang told the audience. "Rooted in a distinctly commercial genre, it took visionary talent to elevate wuxia into high art."

Set in 19th-century China, it tells the story of a legendary warrior (Chow Yun-fat) who entrusts his sword to his lover (Michelle Yeoh), only for it to be stolen by the mysterious Yu Jiaolong (Zhang Ziyi), setting off an epic saga of love, betrayal and redemption.

In a pre-screening discussion, Lee reflected on the film's enduring impact and the diverse cast and crew that brought it to life.

"We had an incredible mix of talent from the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong and overseas Chinese communities," said Lee. "Together, we created something greater than the sum of its parts, what I called a pursuit of the 'hidden dragon' within us."

Lee, who was born in Taiwan to parents from the Chinese mainland and later studied in the United States, described the film as a personal cultural exploration.

"My heritage is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture," said Lee, who has won Academy Awards for Best Director for two other films. "When making this film, I traveled across China from the deserts of Xinjiang to bamboo forests in the south. I saw the blue skies, green waters and felt the spirit of the land. That spirit became part of the film."

For Lee, the character of Li Mubai portrayed by Chow symbolizes a restrained, idealized hero. "He's like a gentleman warrior, calm on the surface but with a storm within. That's the hidden dragon," Lee said. "Perhaps I was chasing an imaginary China — a place of elegance, depth and contradictions. And through this film, all of us came together to find that dragon."

Lee emphasized that Chinese martial arts in the film were more than stylized action, they were philosophy in motion.

"Martial arts reflect the Tao — the natural way of the universe. In Eastern culture, we believe in something bigger than ourselves. Harmony, restraint and respect guide our actions," he explained. "Even drinking tea or engaging in combat is part of that philosophical framework."

Yet Lee admitted that his artistic sensibilities often blend East and West. "Though I come from the East and value harmony, my real talent lies in Western drama," he noted. "So with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, I combined both philosophy and action, restraint and drama, all within the framework of a love story."

Zhang Ziyi, who rose to international fame through the film, shared how her six years of dance training helped her meet the film's physical demands. "Dancing taught me discipline, resilience, and how to express through movement," Zhang told the audience.

"But becoming this almost mythical warrior fighting on rooftops and flying through bamboo forests was unlike anything I imagined," Zhang said, adding that she felt honored and grateful to be part of the film.

The film's blend of visual poetry and martial arts redefined the wuxia (martial arts fiction) genre for global audiences. "We didn't just make a martial arts film," Lee said. "We made a film about love, loss and longing about culture, identity and imagination."

Yang noted that the film's global success also sparked a resurgence in martial arts cinema. "Western audiences weren't familiar with the genre at that level," she said. "But Crouching Tiger changed that. It opened the door to new possibilities in Asian cinema. A genre that was fading was suddenly revived with elegance and force."

Audience members at the Academy Museum screening shared their appreciation. Among them was veteran Hollywood film producer Donna Smith, former president of physical and post-production at Universal Pictures.

"Crouching Tiger is truly one of my favorite films," Smith told China Daily. "We actually did another presentation of the film just a month ago in Minneapolis. It's a film with an enduring legacy that continues to unite East and West."

Another attendee, Rich Erickson, said the film still feels fresh even after 25 years. "The first time, I was captivated by the action," he told China Daily. "But now, I'm even more moved by the emotional resonance and the philosophy behind the martial arts. It's truly timeless."

Carlos Salazar, who first saw the film when it was originally released, offered a similar observation. "The visual was stunning, but it's the emotional depth and the story that keep me coming back," he said. "It's one of my all-time favorites."

renali@chinadailyusa.com